Christmas & New Year Trading

Website: Open 24/7 for on-line ordering.

Customer Service/Warehouse: Closed 12pm Monday 23rd December 2024, re-opening 8:30am Thursday 2nd January 2025.

All orders placed over the holiday period will be processed in the New Year.

We wish all of our customers a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.

Japanese vs German knives

Japan and Germany are thought of as two of the most important centres of the world’s kitchen knife industry, with Solingen in Germany and Seki in Japan at the heart of knife production in those countries. Both countries produce highly sought-after knives for professional kitchens — but what makes them so good and how do they differ from country to country?

This post will explore some of the technical differences between traditional German (and more generally, European) knives and kitchen knives that have their basis in the long-standing tradition of sword making in Japan.

Below is a table outlining the main attributes of the two knife styles:

| Attributes | German | Japanese |

|---|---|---|

|

Bevel |

17–22 degrees |

12–17 degrees |

|

Bolster |

Typically yes |

Traditionally no, though modern blades do carry them |

|

Handle |

Ergonomic grip with full tang |

Traditionally cylindrical with partial tang |

|

Shape |

Slight curved edge with wide-angled tip |

Straighter edge with acute tip |

|

Weight |

Heavy |

Light |

|

Thickness |

Thick |

Less thick |

|

Steel |

Softer, Rockwell: 56–58 |

Harder |

For a greater explanation of the attributes used to measure the performance of a knife, keep reading.

However, it is important to acknowledge that the distinction between the two styles is increasingly small, with both regions borrowing design elements from each other and a growing prevalence for hybrid knives that include features of both styles in different proportions.

Variations in steel-making techniques also mean that where certain mixes of steel were traditionally thought of as harder or softer, new industrial processes tend to blur those distinctions.

Therefore, for the sake of an overall picture, we are forced to talk in generalisations when comparing styles.

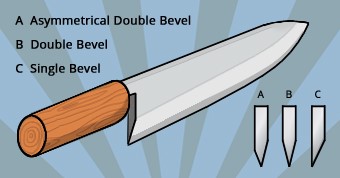

Bevel

Also known as the grind, this is the angle at which the blade is sharpened. When observed under a microscope, many edges have a V shape where both sides of the blade are sharpened. Some Japanese knives are only sharpened on one side, creating a more acute angle shaped like a chisel. A number of variations on these basic shapes can also be found.

German: Traditional European chef’s knives are ground on both sides to a typical angle of between 17 degrees and 22 degrees from the vertical line running through the centre of the blade. A common angle to be found on German knives is 20 degrees.

Japanese: Japanese knives made in the traditional style carry a grind on one side only. This creates a much sharper blade, but also limits how the blade can be used. However, the majority of modern Japanese knives are ground evenly on both sides, or are ground in such a way that one side features a more acute angle than the other (asymmetrical), increasing versatility while retaining sharpness. Japanese knives with a symmetrical bevel typically feature angles of between 12 degrees and 17 degrees.

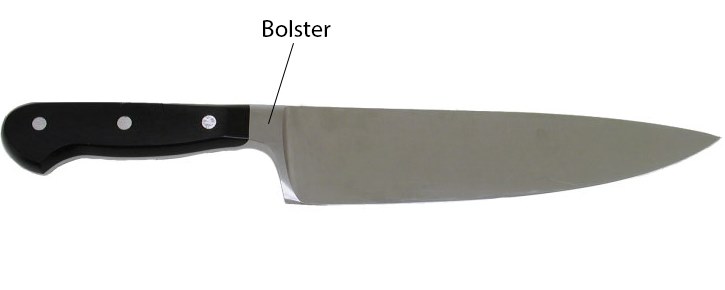

Bolster

This is the wide piece of blade at the handle end of the knife that prevents the hand from slipping on to the edge.

German: Bolsters are a standard feature on German knives. They help to both balance the blade and prevent the hand from slipping. Bolsters can make sharpening more difficult in certain circumstances. Some knives feature a ‘half bolster’, which reduces weight and allows for a greater variety of grip.

Japanese: Many traditional Japanese knives feature a cylindrical handle with no bolster. This greatly reduces weight and allows for a freedom of movement when holding the knife. However, combined with the typical sharpness of a Japanese blade, the lack of bolster can lead to accidents. More and more Japanese knives carry a Western-style handle. These can feature a bolster, half bolster or none at all.

Handle

The shape of a handle can affect how the knife is used and the jobs it can be used for. Handles also include the tang — a length of steel that is part of the same metal of the blade which runs continuously through the handle, either to the entire length or part of the length.

German: German handles are typically designed to fit perfectly into the hand. This contouring effect creates a firm and balanced grip. However, combined with the bolster, hand movement can be restricted. Whether or not that is a bad thing will depend on the task that needs to be performed.

German knives often feature a ‘full tang’, typically held on with rivets. This design adds strength and durability to the knife.

Japanese: Traditional Japanese knives feature a cylindrical handle, tapered slightly wider at the end away from the blade. This can allow for more versatile cutting strokes — perfect when delicately slicing fish. Many of these handles also feature partial tangs, though this is often down to the manufacturer’s preference. Some modern or hybrid Japanese kitchen knives are designed to carry a Western-style grip and full tang.

Shape

The shape and curve of the blade impacts the type of job that can be done with the knife.

German: The shape of a knife alters according to the use for which it is specifically designed. However, general trends can be seen between knives from different regions of the world. Typical German chef’s knives feature a slightly curved edge (belly) that facilitates a rocking chopping motion. The tips of German knives also feature a relatively wide angle.

Japanese: Though there are many different shapes and styles of Japanese knives, they tend to have a straighter blade with an acute angle at the tip. However, specialist knives such as the deba — for use with fish — also feature a belly, though still carry an acute-angled tip. Other knives, such as the takohiki, feature almost no tip at all, with the blade finishing at a right angle.

Weight

Factors that affect the overall weight of the blade include its thickness and whether or not it carries a bolster.

German: Traditionally a solid, heavy knife. This is partly due to the bolster. In general, German knives are more durable; hence, they can be used for more robust jobs without the fear of chipping.

Japanese: Most consumers would expect a traditional Japanese knife to be lighter than a German knife. Such knives should not be used around bones, unless they are specifically designed for such a purpose, as they may be liable to chip or crack.

Thickness

Blade thickness will affect how sharp the knife is, as well as how thinly it can slice food.

German: As you might expect from a heavy knife, the blades that come with a German knife are usually on the thick side. This makes the German chef’s knife suited to a greater range of jobs. The bolster is typically the widest part of the blade.

Japanese: Japanese knives are thought of as thinner and sharper, delivering a finer cut when dealing with delicate food such as fish and certain vegetables. Japanese knives in the Western style or hybrid knives trade some of that thinness for robustness.

Steel

The issues that affect a steel’s performance include the elements added to the iron — such as carbon, chromium and molybdenum — and the manner in which the metal is heat-treated. A steel’s hardness is measured using the Rockwell scale. In general, the higher up the Rockwell scale a steel is, the less likely it is to wear down, but the more prone it is to chipping. However, these performance issues can be affected by the heat treatment that the steel has undergone during forging.

German: Generally, the steel used to make German knives is softer than that used for traditional Japanese knives. They tend to be around 56 to 58 on the Rockwell scale, though they can range through to the early ‘60s’. This adds to their robustness (as they deform on a microscopic level, rather than crack) and ease of sharpening. However, modern steel-making techniques mean that knives can be given various attributes, resulting in steel that is hard but easier to sharpen, and vice versa.

Japanese: These harder blades are famed for holding their edge for longer. The steel often registers between 60 and 63 on the Rockwell scale. The drawback to this can be a greater tendency to chip or crack. What must be kept in mind, however, is that modern Japanese knives use similar steel to modern German knives, reducing the overall performance difference. Where once there was a choice between carbon steel and stainless steel, there is now a range of steels that can be used, along with a number of different ways of heat-treating the steel in order to produce specific characteristics within the steel. These techniques are available to both German and Japanese knife producers.

Final thoughts

German knives are considered solid and robust, with a thick blade and a reassuring heavy feel. Their moulded handle allows for a firm grip to deal with tough jobs. Japanese knives are typically thinner, sharper and more agile, making them suited for delicate, intricate cuts and slices. However, modern knife-making techniques have generally removed many of these distinctions, with each country now offering a vast range of different knife styles.

To pick the knife best suited for your work, it is recommended that you consider the specific steel-making techniques employed in their construction and read feedback comments from fellow chefs. Only that way can you be sure that the knife you have chosen is right for you.

For more information on knives, click on the links below:

- Boning Knife Guide

- Paring Knife Guide

- Filleting Knife Guide

- Pastry knives

- Santoku Knives vs Chefs Knives

- Guide to Carving and Slicing Knives

- Frequently Asked Questions About Granton Edge Blades

- 10 Most Common Chef Knife Care Mistakes and How to Stop Making Them

- How to sharpen your kitchen knife

14 December 2017